Homeland Economics: a collaboration between Miel Paredes and Rebecca Scheer

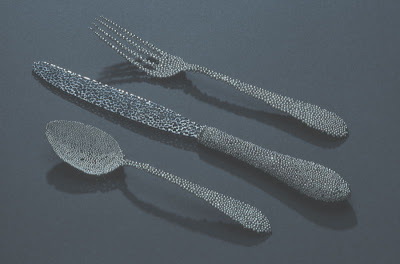

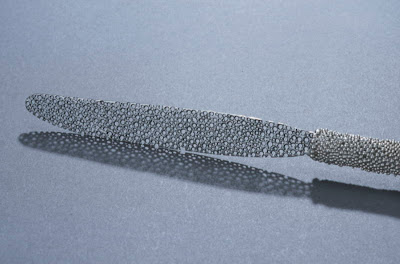

The collaborative project we envisioned was this: Miel raises a vessel (gravy boat or creamer) and Rebecca deconstructs it. In other words, Miel transforms a flat sheet of metal through arcane but skillful wielding of the hammer into a graceful, useful serving dish and I ruin it (in an artful way).

Viewed from the inverted lens of the art world, it would seem that I have co-opted a perfectly useful object redolent of decadent Western excess toward the subversive aims of perfectly useless art with a capital A. Perhaps I question the nostalgic colonial Williamsburg appeal of the crafts in a post-post-industrial age. Perhaps I harbor a socialist's disillusionment with hand craft a la William Morris. Perhaps I do, but please note that I shed real tears as I pierced the vessel with the "old fashioned" style waste-overflow drain pattern visible on the bottom.

Viewed through the fisheye lens of business economics, with the exception of a few rarified market niches (collectors, historians, academia, and really smart people like you), the singular American craftsperson is irrelevant to modern society. Goods for our homes and bodies are designed by global celebrity designers (nice work if you can get it); the physical task of creating material goods is outsourced to the current location of cheapest labor (not such nice work). From Walmart to IKEA, the government sanctioned/supported business model is the same. The market is by no means free; the entrance fee is affordable only to corporate entities.

For a plethora of stuff, we have not even traded but have actually discarded many valuable yet intangible benefits of the local and real economy including: respect between the makers and users of objects (think about built-in-obsolescence), the value of skillful labor to human life, the value of human labor vs. machines, the value of human life vs. limited liability (think about safety recalls), and the value of human relationships over financial contracts. For these losses I also weep.

Miel Paredes and I are members of a weird club of academic entrepreneurs who cobble together a living from teaching our art/craft/working process, making work for galleries, making jewelry for craft/art fairs, and other odd jobs loosely metal related. At times, it is exhilarating to so closely link the practice of our craft to our personal economies. At times, it's merely draining.... ba dum bum. Miel essentially agreed to be the straight (crafts) "man" in our collaboration, while I got to deliver the (artistic) punchline. It isn't fair but that's precisely the point. The joke's on all of us.

Rebecca Scheer

September 3, 2009

Please also visit:

www.mielmargarita.com

http://emmalinestudio.etsy.com/

http://scheersilver.etsy.com/

www.scheersilver.com